The outlines of New Jersey’s demographic future have long been in place. In fact, the foundations of that future were foreordained by two events that took place many decades ago—the great American postwar baby boom (1946-1964) and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The baby-boom generation has long been the dominant demographic dynamic in New Jersey—and the nation—because of its sheer size. It will still be a powerful force 10 years from now, but by then it will be challenged in importance by the increasing size of the state’s minority (soon to be majority) populations—thanks to the increase in non-European immigration over the past 45 years. As a result, New Jersey in 2021 will be characterized by a heavily white, aging baby-boom population, and a younger, more diverse population that will be approaching majority status.

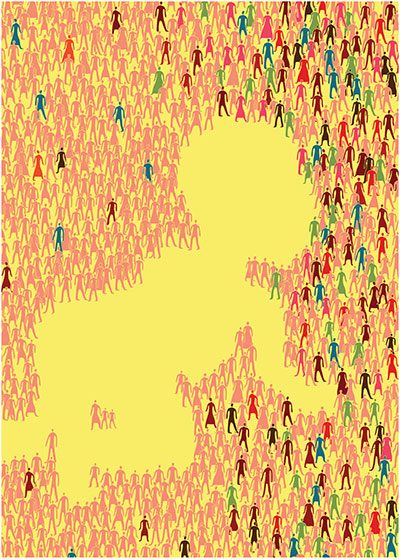

By 2021, the final movement of the baby-boom generation into its senior years will be well under way. This will be a demographic event of epic proportions. The baby boom consists of that postwar generation born between 1946 and 1964. It is the largest generation ever produced in the history of the United States—77 million strong, and in New Jersey, approximately 2.6 million. Visually, it has been the classic pig in the demographic python. By 2021 many members of the generation will be well down the length of the python.

The baby boom has dominated New Jersey throughout each stage of its life cycle, continuously sending social and economic tidal waves across the Garden State, defining the state’s culture and every demography-driven housing era. It was originally the Hula Hoop generation in the 1950s and was the foundation of the greatest housing production period in the state’s history. Young households, with their baby-boom children, moved into Levittown-style dwellings at the rate of 1,000 per week for 1,000 straight weeks, driving the production of approximately 1 million units from 1950 to 1970. As the baby boom roared, tract-house New Jersey emerged, sprawling across the state’s once-agricultural landscape, overwhelming its school systems and educational facilities.

The baby boom then became the Woodstock generation in the 1960s and began to inundate our colleges and universities, spawning a dramatic expansion of higher education and campus housing. By the beginning of the 1970s, the baby boom began to enter New Jersey’s housing and labor markets in full force, with garden apartments and jobs penetrating deep into and changing the structure of our suburbs. It then formed the yuppie brigades of the 1980s, and entry-level homeownership quickly followed. Grumpies—grown-up mature professionals—supplanted yuppies as the 1990s unfolded and the baby-boom generation moved into the child-rearing stage. The demand for family-oriented, single-family shelter surged, and a huge web of trade-up housing markets eventually emerged. Then, as the new century unfolded, the baby boom, riding the crest of its high income and best earning years, powered the wave of McMansion building, further changing New Jersey’s housing landscape.

But then advanced middle age hit the boomers with a vengeance. Age-restricted, active-adult communities proliferated as the leading edge of the baby boom became empty nesters. And, as was the case several times in the past, developers overshot the mark, leaving a vastly overbuilt market.

The latest signature date for this generation is January 1, 2011, when the first boomers (born in 1946) will hit 65 years of age. This date will mark the start of a vast unfolding of the yuppie elderly market. By 2021, all baby boomers will be between 57 and 75. Eight years later, 2029, every living boomer will be 65 or older. The baby boom’s seven-decade-long shaping of culture and housing in New Jersey will have reached its final stages—and the state will be facing the prospect of a baby boom-less demographic future. The baby boom’s final impact will probably be the proliferation of continuing-care facilities.

In 2021, baby boomers will find themselves in an economic world very different from the era of affluence and optimism in which they grew. During their lifetime, the boomers redefined consumer behavior in ways that were reflected in New Jersey, from the onset of regional malls to the emergence of power centers and big-box retailers. While our crystal ball is cloudy, the great recession—which started in December 2007 and technically ended in June 2009, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research—and its aftermath are likely to have fundamentally redefined and reshaped American economic reality. For many boomers in 2021, the very idea of a prompt retirement may have faded. Because of drastically changed financial circumstances, many more boomers are likely to be working later in life than only recently anticipated. A key question is whether or not the economy will be able to accommodate them in terms of their revised employment and income expectations.

The baby boom’s journey through the coming decade will be paralleled by a transformation of New Jersey’s racial and ethnic composition. The state is already far more diverse than the nation as a whole, currently ranking third among the states in the percentage of the population that is foreign born. In 2009, according to the Census Bureau’s latest American Community Survey, about one out of five (20.2 percent) of all New Jerseyans is foreign born, compared to one out of eight (12.5 percent) for the nation as a whole. There are two major reasons for this. The first is the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which reduced immigration from Europe and increased it from nations that had previously been excluded. This shifted the origins of the largest flows of population into America from Europe to Asia and Central and South America. In addition, the act increased the allowable size of the flows. The second reason is that New Jersey has always been an important immigration gateway to the country, magnifying the effects of the Act of 1965 here. The end result was New Jersey’s second great wave of immigration.

The fact that one out of five New Jerseyans is foreign born is not an unusual situation in the long sweep of American history. In 1965, only 10 percent of the state’s residents were foreign born. A doubling of share may seem to be a dramatic change, but, 1965 is likely to have been the least diverse period in the state’s history. In 1920, at the end of the first great immigration wave, 25 percent of New Jerseyans were foreign born. But the floodgates were tightly closed by the Immigration Act of 1924, and the share of the population that was foreign born declined for the next four decades until the immigration laws were again changed.

The surging growth rates of Asians and the increasing critical mass of Hispanics ensure that by 2021, the state’s white (non-Hispanic) population will be approaching minority status, although it may take the balance of the 2020s for this transformation to be fully realized. Hispanics already have surpassed African-Americans as the state’s largest minority. Within two decades, Asians will be the second largest minority in New Jersey. And, just as the differentiation among European nationalities faded with time, so will the differentiation among the new immigrant communities.

The intersection of increased diversity and an aging baby boom will serve to redefine New Jersey in 2021 and beyond. It will be a time when the state’s labor force will be in the process of being completely replenished and retooled. The state’s economy will become ever more dependent on a newly diverse population. During the past two decades Asian groups in particular have had a significant positive effect on the state’s high-tech industries, particularly telecommunications. By 2021, first- and second-generation immigrant populations should increase the state’s ability to replace departing boomers in our sophisticated knowledge-based labor force and service economy.

In addition, the second great immigration wave and its children will likely be the purchasers of the former homes of the baby-boom generation. Ten years ago, the results of Census 2000 showed a substantial suburbanization of diversity beginning to take place in New Jersey. This trend will continue through 2021. Newer immigrants will continue to sustain and bolster housing demand in the state’s urban areas where they have historically concentrated, but more established immigrant groups will also increasingly reside in New Jersey’s suburbs.

James W. Hughes is dean of the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers. Joseph J. Seneca is university professor of economics at the Bloustein School.